In the land of Orïsha, King Saran rules with an iron fist. A decade before, he had every last maji executed in a power grab that eradicated magic and thrust thousands into inescapable poverty. Denied access to the magic they would gain when they were older, the white-haired children of the maji, known as divîners, became the slaves of the empire, the lowest of the low. There is no escape and no hope, just pain and suffering and bondage. Until one day when a magical artifact reemerges from the sea.

Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone tells the story of how pampered Princess Amari teams up with rebellious divîner Zélie and her un-magicked brother Tzain to restore magic to Orïsha. While on their quest, they are chased across the kingdom by Prince Inan, a boy driven equally by self-loathing and duty to his country. At his father’s behest, Inan must stop the trio, even if it means murder. Allegiances are forged and shattered, promises made and broken, and hearts won and lost. This is Zélie’s only chance to save the world, but is she strong enough to beat back an army of soldiers and a nation filled with bigots?

Buy the Book

Children of Blood and Bone (Legacy of Orisha)

Adeyemi poured in elements of Nigerian and Yoruban culture, plus a dash of Brazil. Candomblé (Chândomblé), Ilorin (Eloirin), Lagos (Lagose), Calabar (Calabrar), Warri, Zaria, Ibadan, etc. are all real; see also jollof rice and honey cakes. Many African languages use “baba” for father. In Yoruban tradition, an Òrìṣà is a deity or spirit with divine power. The clothing, structures, food, environments, and animals are brimming with West African and Yoruban influences.

Too often, spec fic authors draw inspiration from Western/European traditions but insist they’re neutral literary devices. Fantasy is drowning in elves, fairies, vampires, and wizards, and too many authors act like they’re fundamental aspects of fantasy. Except they aren’t. Or, they are, but only when writing within a Western/European framework. By rejecting that, Adeyemi simultaneously rejects whiteness as the default mode and celebrates Black culture. In Children of Blood and Bone, she’s offers a standard epic fantasy but without any white trappings. Although there are plenty of recognizable elements, the default here is strictly West African rather than white. This shouldn’t be a revolutionary act in 2018, but it certainly is when the publishing industry continues to value books about POC written by white people over POC authors. And if you think POC readers can’t tell the difference between a white tourist and #ownvoices, I have some shocking news for you.

This novel wouldn’t exist without a Black author. Adeyemi’s experiences as a Black woman in Western society permeate the novel. When Children of Blood and Bone talks about systemic oppression, colorism, and privilege, it isn’t subtext; it literally is the text. In interviews, Adeyemi has said she was inspired as much by Black Lives Matter as her Nigerian roots. And the threads of that movement and everything it reacts against are readily apparent. Every hostile interaction between Zélie, Tzain, and the soldiers mirrors the real world experiences and cell phone videos of police brutality. The open disdain of the kosidán toward divîners, of the viciousness of those in power over those who are powerless, of the aggression of those who directly benefit from the system against those the system is structured to disenfranchise.

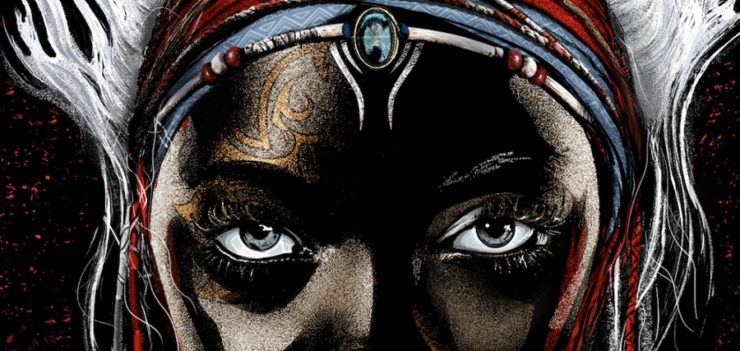

In Orïsha, divîners and maji have dark brown skin and white hair (without magic their hair is straight, with magic it’s tightly curled), and those in power have light brown skin. We don’t often see colorism explored in YA fantasy, whereas racism gets plenty of play, albeit frequently poorly handled by authors who don’t know what it’s like to be oppressed by it. Colorism can drive African Americans to bleach our skin and hate our wide noses. It means subjecting each other to the paper bag test, the door test, the comb test. When white is the ideal, the non-white must be molded, modified, and mutilated.

Through Amari and Yemi, Adeyemi explores the harsh reality of colorism and privilege. Light brown skin denotes high rank in Orïsha. The royal family are embarrassed by the past intermixing of maji and royal kosidán, a past that reveals itself in Amari’s slightly darker skin and lighter hair. In contrast, Yemi, Zélie’s hometown nemesis, has coconut brown skin but was brought low by her father’s sexual impropriety. Yet she uses her lightness as a pedestal to raise herself above Zélie. She is better because she is not divîner, as evidenced by her light skin and dark hair. Amari discovers that imbalance early on and uses the leverage provided by her lighter skin tone to protect and aid the divîners. Inan, too, gets first-hand experience with colorism, but chooses a different path. In a lot of ways I related to Amari. I’m light-skinned enough that most white people assume I’m white. Like Amari, I have the dual role of advocate and ally. I fight side by side with my people while also using my privilege to hold open doors that are closed to those darker than me and uplift their voices whenever possible.

I was also struck by the complexities of morality in the novel. YA often falls back on the binary of good and evil. Clearly King Saran is a sadistic monster using the his past suffering as a flimsy excuse for inflicting great pain on the world. And although his son Inan follows in his footsteps and wants to see the maji permanently stopped, his intentions become less sinister as the story progresses. He does bad things for good reasons and good things for bad reasons, all in the name of keeping his country whole. He and Amari both want Orïshan society to be less bigoted, but unlike his sister Inan isn’t interested in fixing the system. It’s one thing to argue for peace and equitability between the brualized and the brutalizers (as Amari does) and another to tone police the oppressed into capitulating to their oppressors (as Inan does).

Not that Zélie and the depowered divîners are any less ethically hazy. Zélie isn’t interested in changing hearts and minds but in smashing the system into pieces. Between all that bloodshed and destruction they make some pretty valid points. They’re pushing back against years of violent abuse and horrific exploitation by kosidán. Is it so inexcusable that when confronted with the awful truth of oppression, those whose blood and bones built the world would react with rage? That when given the opportunity to overthrow the people who destroyed entire cultures, some might turn to vengeance and punishment? But both Zélie and Inan’s goals are incomplete. Neither seem to know what comes after the revolution. Inan offers divîners no path out of subjugation and Zélie no opportunity for kosidán to unlearn their biases.

I could keep writing for hours more—I haven’t even gotten into how Adeyemi tackles generational trauma, PTSD, slavery, or gendered violence—but for the sake of my word count and my editor’s sanity, I’ll wrap this up. Children of Blood and Bone is devastating and daring. It’s not perfect (what novel is?). The pacing is a bit off at times, and juggling three distinct POVs was occasionally overwhelming. I wasn’t so much bothered by certain characters constantly changing and rechanging their opinions of each other. If you spend as much time with teenagers as I do, you’ll know that comes with the territory. Hormones, impulse control, and everyone acting extra all the damn time is par for the adolescent course. Sometimes I feel like adult reviewers of YA fiction forget that the leads aren’t adults who think they have all the answers but kids still trying to figure it out.

Anyway, I loved this book and cannot wait for the rest of the trilogy. Tomi Adeyemi’s writing is beautiful and immersive. She took some majorly heavy topics and wove them into a intense, action-packed story about love, loyalty, and fighting back. Remember that scene in Black Panther where Okoye and Nakia beat the living daylights out of a bunch of white dudes in a South Korean gambling hall? Distill that feeling of powerful Black girl magic into book form and you’d get Children of Blood and Bone.

Children of Blood and Bone is available March 6 from Henry Holt & Company.

Listen to an excerpt from the audiobook here.

Alex Brown is a YA librarian by day, local historian by night, pop culture critic/reviewer by passion, and QWoC all the time. Keep up with her every move on Twitter, check out her endless barrage of cute rat pics on Instagram, or get lost in the rabbit warren of ships and fandoms on Tumblr.

This is on my to be read pile, I cannot wait to read it.